If decorating this jacket is my ticket to membership in the twin cities punk scene, why haven’t I finished it yet?

By Quinn McClurg

Repetition is the means by which one deepens a ritual; a ritual is a means by which one distills meaning. My undistilled meaning sits to the left of me, a half-stitched jacket, thread still slack, longing for the repetition of needle and string. I reach out, flex my fingers, then turn away. This is the ritual of creating a battle jacket, or, in my case, being half-way through creating one.

Before I describe this process any further, it is integral to understand how this process came to be. It’s World War II. You, a pilot, fresh out of training, are handed an A-2 jacket, standard issue, made to travel with you wherever you go. This is to become your uniform, your primary means of identification, and your pride and joy. When each new mission one disembarks on has the potential to be the last, a thoroughly decorated jacket was a symbol of resilience, survival, or a means of identifying a body. So, squadron patches were sewed solemnly next to rank mark stitches, mission numbers laid painted next to kill counts, and painted murals (ex. a pin-up girl, a cartoon character, a lucky charm) reigned over all other details; any shred of home, comfort, or confidence that a pilot could carry with them to the battlefront was invaluable.

The popularity of personalizing jackets is best demonstrated by how fast it spread to other subcultures. After World War II, bikers and racers sew personality and other identifiers into their jackets, favoring denim instead. Bomber jackets became bikers’ “cut offs,” then finally, when the practice ended up in the hands of punks and metal fans, the “battle jacket” was born. And ideally, like the pilots of long ago, a good punk survives long enough to wear their jacket as much as possible.

But why would you ever take it off? The history of the punk battle jacket was born out of necessity, often made with only whatever materials were available, and designed to have as much utility as possible. It is not uncommon to see a jacket that is more patches than denim, has patches held on by dental floss, or has supplies incorporated within (stores of safety pins, secret pockets, rocks sewn and spikes in for self-defense, etc.); the uses and customizations of a battle jacket are as unique as the person wearing it, changing and evolving with their survival.

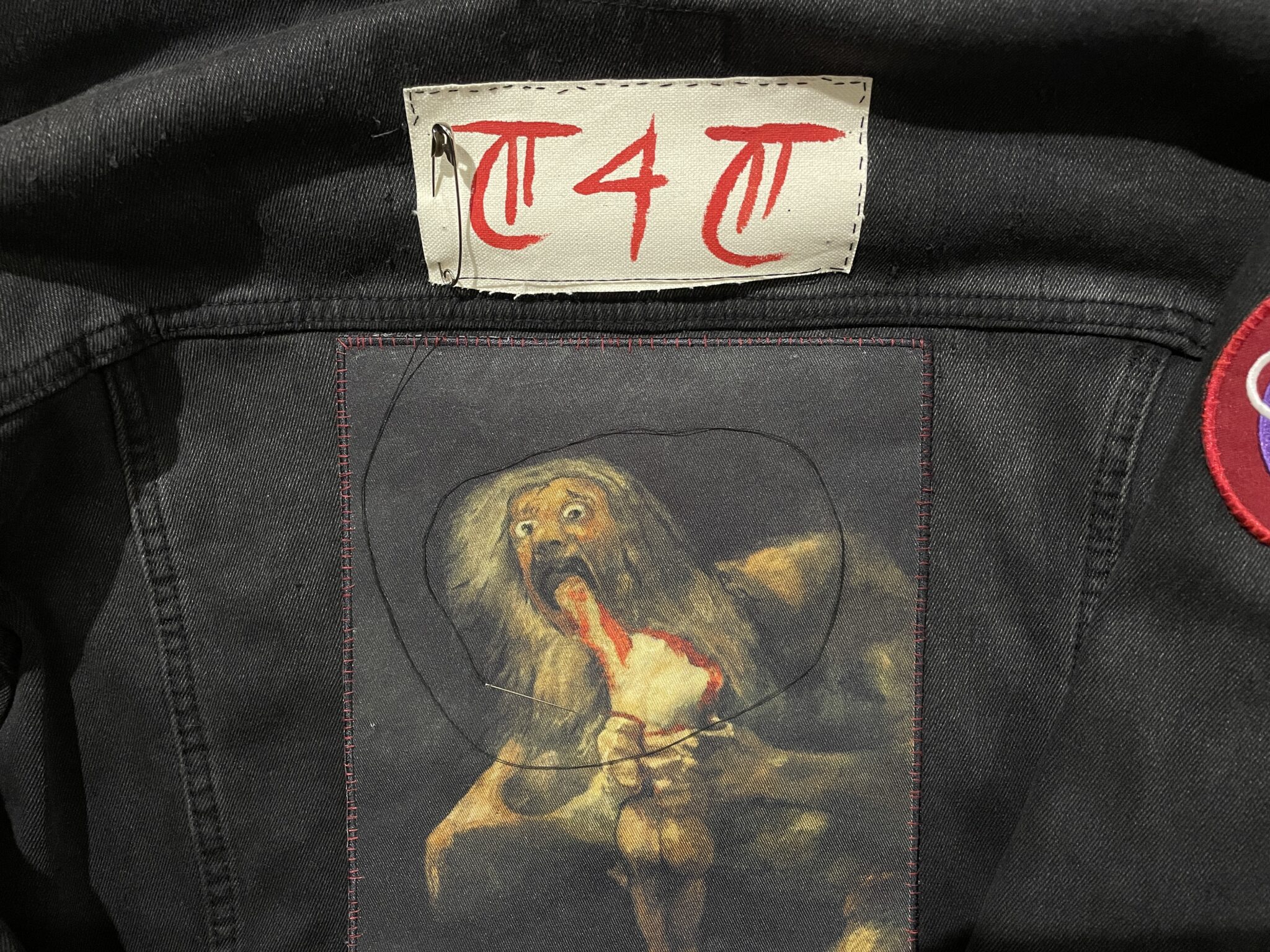

We return to my battle jacket, that black denim collection of peeling patches and safety pins. If this jacket is my ticket to becoming an official member of the Twin Cities punk scene, why haven’t I finished it yet?

Well, battle jackets aren’t made just to be jackets, they’re made to be your identification, your second skin, something as meaningful to you as it is inseparable. The process of making a sufficiently meaningful jacket isn’t reliant on some esoteric brand of grunge alchemy, but rather on two factors: intention and time. Without enough time and intention, both the jacket and the wearer may never form a cohesive identity. Time deepens identity as ritual deepens meaning; every stitch must be hand-sewed, every patch must be handmade, and every action must be confident and meaningful and proud. This is usually where I falter and stop.

Although I’ve done my time in the punk scene grime and have been to more concerts than I can count on ten pairs of hands, confidence has never come easily to me, especially when regarding my identities that are alternative to what is homogenous or culturally accepted.

I was raised in central Wisconsin and mostly fit into my normative Wisconsin. Unlike some acquaintances I’ve made who have grown up in the Twin Cities, I had little to no exposure to queer or transgender communities before moving here. However, after moving here and stumbling into my first Twin Cities show, I’ve found my way into groups of people who are queer, trans, and otherwise non-hegemonic. After enough time and exposure, I came to understand that I have always been part of those communities, but had the means to realize it. It took me about two years after moving out of my hometown to realize that I am a trans woman.

This is what gives me pause, the half-embroidered pronouns and a half-finished canvas “T4t” (trans loving trans) patch. I’m just beginning to understand these things myself and proudly wear them internally, so externalizing these identities seems hasty, and almost ill-advised. Although the Cities can be considered a safe space for trans individuals most of the time, having a constant, visible indicator of my gender identity could potentially paint a target on my back, threatening my means of survival. So, I maintain a low profile when I need to, and give occasional thanks that I can still pass as a man.

Like every other title or label, I imagine wearing it enough will make it truer, and, like an old A-2 flight jacket, that I will only grow more comfortable wearing it; eventually, maybe my jacket and my identities will have survived long enough to be well-worn to the point of love.

This entire article isn’t to say that I’ve given up on my jacket—the longer it sits in its heaping incompletion upon my dresser, the more my hands itch to finish it. I don’t know how long it will take for me to integrate my trans- and polyamory-indicating patches, but I’ll have plenty of time to mull it over while I sew on my back patch. If you ask any punk, they won’t hesitate to say those are the hardest to sew on—here’s to hoping I don’t run out of dental floss.